A “lollipop” route is one which starts and ends at the same trailhead and at some point splits off into a loop off of that main trail. Hence the shape of a lollipop. The McGee Creek trailhead had always intrigued me as a place that offered a route that would encompass a lot of variety. This route didn’t disappoint in the area of variety, but would prove to be the most challenging trip of 2022. This adventure reminded me of the importance of preparation, in terms of route planning, into every trip whether big or small, on or off trail. Had I properly prepared for this route, I probably would have never attempted it.

Day #1

Daily Miles-17.03

Total Miles-17.03

Daily Elevation Gain-4562 ft

Daily Elevation Loss- 3267 ft

It was a couple weeks after the height of fall colors that Pablo and I headed to the east side of the Sierras, my happy place. The 4 ½ hour drive flew by and in no time we were at the trailhead and in temperatures in the high 20s. Dressing warmly, we headed into the mouth of the canyon.

We were hit almost immediately with views of the stunning geology of red, white and gray peaks all around us. The unique striated, metamorphic red rocks all mixed together with granite creates a show like nowhere I have ever been in the Sierra. Most of the Aspen color had faded and/or had been stripped by the storm the previous week, but the ground was glowing with oranges and reds.

Following McGee Creek, we crisscrossed the water a few times on rocks, logs and downed bridges and after about 5 miles we took a right turn for our counter clockwise lollipop route.

We continued up the McGee drainage passing one frozen waterfall after another until reaching Big McGee Lake at about 10,500 feet.

The lake sits directly under Red and White Mountain (at 12,816 ft) rising on the west. Its beautiful and deep waters looked cold in the Autumn winds of the day. It was about 7 miles to this beautiful lake and we still had three more miles from the top of McGee Pass.

As the climb continued, my energy immediately sapped. I had nothing left. My legs were full of lactic acid making each step very difficult. And now, breathing at over 10,000 feet (coming from almost sea level just that morning) was taking its toll on my lungs. We had close to 1500 feet left to climb over a little less than three miles (150 story building). Every step was difficult. It was as difficult mentally as it was physically as we were walking into an area without any sense of scope or size. Everything around us was a mixture of red, white and gray. Shale and rock everywhere. If we turned around we would see Big McGee Lake and Little McGee Lake but ahead was just rock. Not a single living thing to be seen.

And we couldn’t see McGee Pass at 11,895 feet ahead of us because there were so many false summits between us and the true summit. Both Pablo and I were wearing colors very similar to our landscape and he got so far ahead of me that there were times I couldn’t pick him out from the landscape itself. Finally, from afar, I watched Pablo crest what I assumed was the true pass and disappear. I’d asked Pablo many trips ago not to announce the pass if he was in front of me so that I could experience it the same way that he did. Today, I almost wished I hadn’t asked this of him. I was completely spent and needed to know that he’d just crossed the true pass.

Not long after Pablo, I arrived and crossed McGee Pass. The views were stunning and very different in either direction. To the northeast, nothing but a maze of rock, no view of the lakes or anything living. To the southwest; trees, meadows, water and life. We started our descent and the wind immediately picked up.

We stopped to put on another layer and continued down the trail until we hit the first creek and decided to rest a bit and get water. The wind was really taking its toll on our warmth and we had to have multiple layers on or be moving at all times. With the temperatures around 40 and the winds at about 15 mph, the air felt about 30 degrees and in the short days of an Autumn afternoon, the temps were dropping fast.

I’ve been working hard at getting more comfortable in the cold. For those that know me, they know that keeping my hands warm is one of my biggest challenges. On an earlier trip this year climbing Mt. Whitney, my hands had gotten so cold and caused so much pain, that they had affected my decision making, speech and overall mental capacity. I’d done a lot of research when I got home about it. Doctors have told me that since my hands don’t turn white when extremely cold, I don’t have Raynaud’s, but the symptoms are very similar. Some have suggested that I’m entering hypothermia when this happens to me. This also is not true as I’m able to keep my core temperature stable and the rest of my body is warm. It’s just a hand issue.

Last June, I found a startup company called Toasty Touch. Their heated gloves are different because their gloves are “powered by rechargeable batteries and have tiny, threadlike wires that deliver soothing heat all the way to the fingertips.” The key being that unlike other heated gloves that warm the wrist, back of the hand and/or palm, these gloves heat all the way down each finger. They have three heat settings and on this trip, I found that I could power them up to the highest for a short time before backing down the power level and then eventually turning them off but keeping the gloves on. If it had grown even more windy, I could have placed my rain mitts on top of these gloves to cut the wind as well. They worked incredibly well.

I also made use of a pair of basic blue medical plastic gloves at times. They were no fashion statement but were nice to throw in to cut the wind, but also nice to put on to collect water out of the icy creeks while keeping my hands dry and not causing them to chill immediately in the almost freezing water. Overall, I really felt that I had a system that worked in colder temperatures and was very pleased.

I’ve been working hard at getting more comfortable in the cold. For those that know me, they know that keeping my hands warm is one of my biggest challenges. On an earlier trip this year climbing Mt. Whitney, my hands had gotten so cold and caused so much pain, that they had affected my decision making, speech and overall mental capacity. I’d done a lot of research when I got home about it. Doctors have told me that since my hands don’t turn white when extremely cold, I don’t have Raynaud’s, but the symptoms are very similar. Some have suggested that I’m entering hypothermia when this happens to me. This also is not true as I’m able to keep my core temperature stable and the rest of my body is warm. It’s just a hand issue.

Last June, I found a startup company called Toasty Touch. Their heated gloves are different because their gloves are “powered by rechargeable batteries and have tiny, threadlike wires that deliver soothing heat all the way to the fingertips.” The key being that unlike other heated gloves that warm the wrist, back of the hand and/or palm, these gloves heat all the way down each finger. They have three heat settings and on this trip, I found that I could power them up to the highest for a short time before backing down the power level and then eventually turning them off but keeping the gloves on. If it had grown even more windy, I could have placed my rain mitts on top of these gloves to cut the wind as well. They worked incredibly well.

I also made use of a pair of basic blue medical plastic gloves at times. They were no fashion statement but were nice to throw in to cut the wind, but also nice to put on to collect water out of the icy creeks while keeping my hands dry and not causing them to chill immediately in the almost freezing water. Overall, I really felt that I had a system that worked in colder temperatures and was very pleased.

We didn’t spend long at the creek as we were starting to chill and got back on the trail and moved first through a spectacular meadowy area and then again downhill. Our goal was to make it about 15 miles today which would put us at needing to do about 20 miles tomorrow to be able to camp in Pioneer Basin.

Our map told us that when we reached Fish Creek we would be at about mile 11. But this is when the confusion started. As we reached what the map said was mile 11, we felt like the amount of time and effort thus far felt like a lot more than 11 miles. Up until then we really hadn’t paid much attention to what each of our GPS devices said but as we looked, my phone told me we had come about 13 miles and Pablo’s watch told him we had come about 15 miles. We were somehow off. This meant that reaching our “15 mile” mark on the map, would actually be more like 17-19 miles for the day. A day that had us waking up at 3am and driving 4.5 hours before climbing a constant 10 miles with over 4000 feet of elevation gained. Not easy.

We followed Fish Creek to the JMT/PCT just south of Tully Hole. I’d been here a few times but had completely forgotten what to expect. The JMT/PCT dropped steeply and continued to follow Fish Creek until our “15 mile” map point which computed to 17 miles on my GPS and 19 miles on Pablo’s. We were beat and managed to get into camp and get set up before dark. We cooked in a fading sky and finished our meals and hot cocoas (thanks Pablo) with headlights and temps dropping into the high 20s after a day of nearly 8000 vertical feet.

Day #2

Daily Miles-20.64

Total Miles-37.67

Daily Elevation Gain-5022 ft

Daily Elevation Loss- 3306 ft

Out of the tent around 7:30 in 23 degree temps which meant last night was in the mid teens for sure. Breakfast and coffee as the sun lit the canyon walls behind us. We would have no sun for another hour on the trail.

The JMT/PCT started on a climb which I love on a cold morning to warm the body and soul. After winding its way through the forest, we passed some unnamed lakes plus Warrior and Chief lakes before Silver Pass topping out at 10,739 feet.

The JMT/PCT started on a climb which I love on a cold morning to warm the body and soul. After winding its way through the forest, we passed some unnamed lakes plus Warrior and Chief lakes before Silver Pass topping out at 10,739 feet.

The views northwest on the way up were amazing. We could see the entire Minaret range with Banner and Ritter where I’d been just weeks ago. They felt close enough to touch at times.

We took a break on Silver Pass and enjoyed the warm sunshine with a snack and some water knowing we could fill back up at the bottom of the pass at Silver Pass Lake in less than a mile.

The descent of the pass was beautiful and reminded me of the area just north of Forester Pass called the Bighorn Plateau. I’d been here a few times before.

Continuing our descent and having wonderful conversation, my focus lapsed and I twisted my right ankle. This is my weaker ankle and the one I twist more often. I’ve twisted my ankle so many times that unconsciously I fall into the twist and throw myself to the ground to put as little pressure on my ankle as possible. It looks terrible but saves me from worse injury. Pablo thought I was a goner as he heard me yelp and turned to see me go down. It was bad, but not terrible, and I was up and walking again quickly so as not to let it stiffen up. I’d have to be even more careful from here on out and really try to not twist it again.

Continuing our descent and having wonderful conversation, my focus lapsed and I twisted my right ankle. This is my weaker ankle and the one I twist more often. I’ve twisted my ankle so many times that unconsciously I fall into the twist and throw myself to the ground to put as little pressure on my ankle as possible. It looks terrible but saves me from worse injury. Pablo thought I was a goner as he heard me yelp and turned to see me go down. It was bad, but not terrible, and I was up and walking again quickly so as not to let it stiffen up. I’d have to be even more careful from here on out and really try to not twist it again.

We continued down to Mono Creek and eventually left the JMT/PCT and headed up the Mono Creek Trail. This is a trail I’d never been on but always wanted to visit. We followed this trail for almost 9 miles reaching our lowest elevation of the trip at 7872 ft and then climbing steadily for hours over a well built moderately steep trail that wound in and out of dense pine and aspen forests all the while following the rushing Mono Creek upstream. The other spectacular feature of this trail is that we would pass the entrances for the Second and Third Recesses.

The Mono Recesses are four hanging valleys above Mono Creek. A hanging valley is an ancient glacier valley that is cut into the upper part of a U shaped glacier valley but higher than the main valley. The main valley here is the Mono Creek valley and these four spur canyons empty into Mono Creek. I’ve read about these four Mono Recesses for years and how they each have their own distinct personality. Someday I hope to explore each one, but on this trip I’d get to walk by the entrance to two of them and they were each spectacular.

As the miles ticked by, Pablo stopped and I continued with the agreement that he'd catch me. Pablo had been faster than I’d been on this trip almost the entire time. I expected him to catch me in no time. I kept up what I thought had been the same pace but must have unintentionally kicked my pace up just a bit. Pablo took a while to catch up and we both started to wonder a bit if we shouldn’t have separated. In the end, we both had maps and GPS and both assumed that if he didn’t catch me that I’d wait at the point that we would leave the Mono Creek trail. It turned out that I took a rest about 3 miles before the turn off and he caught me there.

We evaluated the time and how much more distance we had to travel to meet our goal of camping in Pioneer Basin. We were both doubtful that we would reach our goal and began to plan on more than an 8.5 mile partly off trail last day. As we reached the point where we were to leave the Mono Creek trail, the temperatures started dropping and we joined a trail that would prove to be very steep at a few points. We were only 2.5 miles from our planned site at this point but we were both really struggling to find the energy to keep moving forward. We continued hiking.

The Mono Recesses are four hanging valleys above Mono Creek. A hanging valley is an ancient glacier valley that is cut into the upper part of a U shaped glacier valley but higher than the main valley. The main valley here is the Mono Creek valley and these four spur canyons empty into Mono Creek. I’ve read about these four Mono Recesses for years and how they each have their own distinct personality. Someday I hope to explore each one, but on this trip I’d get to walk by the entrance to two of them and they were each spectacular.

As the miles ticked by, Pablo stopped and I continued with the agreement that he'd catch me. Pablo had been faster than I’d been on this trip almost the entire time. I expected him to catch me in no time. I kept up what I thought had been the same pace but must have unintentionally kicked my pace up just a bit. Pablo took a while to catch up and we both started to wonder a bit if we shouldn’t have separated. In the end, we both had maps and GPS and both assumed that if he didn’t catch me that I’d wait at the point that we would leave the Mono Creek trail. It turned out that I took a rest about 3 miles before the turn off and he caught me there.

We evaluated the time and how much more distance we had to travel to meet our goal of camping in Pioneer Basin. We were both doubtful that we would reach our goal and began to plan on more than an 8.5 mile partly off trail last day. As we reached the point where we were to leave the Mono Creek trail, the temperatures started dropping and we joined a trail that would prove to be very steep at a few points. We were only 2.5 miles from our planned site at this point but we were both really struggling to find the energy to keep moving forward. We continued hiking.

After two pretty brutal ascents we crested a ridge that led into Pioneer Basin. The wind immediately picked up and we stopped to put on multiple layers to protect us from the biting wind. We passed 3 or 4 unnamed lakes under a spectacular sky filled with alpenglow that only appears at times and in areas like this one. The peaks inside the recesses blazed in pinks, reds and oranges, The lakes reflected these colors right back at and into us. We stopped to take pictures and take it all in. It was truly some of the most spectacular light I’ve ever seen in my life. We’d not only made it to Pioneer Basin, we’d walked into it at the perfect time. We walked in during the Golden Hour.

Once again, we were able to both set up camp and make dinner in the fading light and once again have hot cocoa under a starry night with a sliver of a moon setting behind the opposite ridge.

Once again, we were able to both set up camp and make dinner in the fading light and once again have hot cocoa under a starry night with a sliver of a moon setting behind the opposite ridge.

Day #3

Daily Miles-8.85

Total Miles-46.52

Daily Elevation Gain-543 ft

Daily Elevation Loss- 3853 ft

Woke up a few times into the night and the temps dropped just above the single digits. I was warm and cozy all night long and had a great cold weather system at this point. I unzipped the tent to see the sun just starting to illuminate the opposite side of the canyon from where we watched it disappear just the night before. What an amazing place to end a day and begin another.

We knew today would be an interesting one but we had no idea just how interesting it would prove to be. After a very relaxing un-rushed breakfast and coffee, we packed up and started our final ascent of the basin. Off trail walking at this elevation is special. With no discernible trail and lots of wide open country, it’s an amazing experience just to stroll in a place you have worked so very hard to get to. We slowly made our way past a few other unnamed lakes and further and further away from Mt. Hopkins and Mt. Huntington while getting closer with every step to Mt. Stanford and Mt. Crocker.

Kim Stanley Robinson, in his book The High Sierra a Love Story, renames this basin "Robber Baron Basin" and as a former 4th grade teacher I can attest to the importance of his re-naming. Robinson says that the name “Pioneer Basin” is a “kind of downer, bringing up as it does the question of why we remember men like that with peak names.” He equates the naming of these four peaks to naming peaks in modern times “Mount Jobs, Mount Gates, Mount Musk and Mount Zuckerberg.” Robinson isn’t saying that some of the above names might be unobjectionable to people with money, only that it’s a bad idea to name mountains after billionaires.

Robinson suggests that we instead focus on women who were left out of the record when naming our peaks and choose to remember some great female writers of American Literature instead. He proposes renaming the four peaks in this basin: Mount Willa Cather, Mount Edna Ferber, Mount Zora Neal Hurston and Mount Edith Wharton. And…even though I had to look up two of four of those…I completely agree. :)

Robinson suggests that we instead focus on women who were left out of the record when naming our peaks and choose to remember some great female writers of American Literature instead. He proposes renaming the four peaks in this basin: Mount Willa Cather, Mount Edna Ferber, Mount Zora Neal Hurston and Mount Edith Wharton. And…even though I had to look up two of four of those…I completely agree. :)

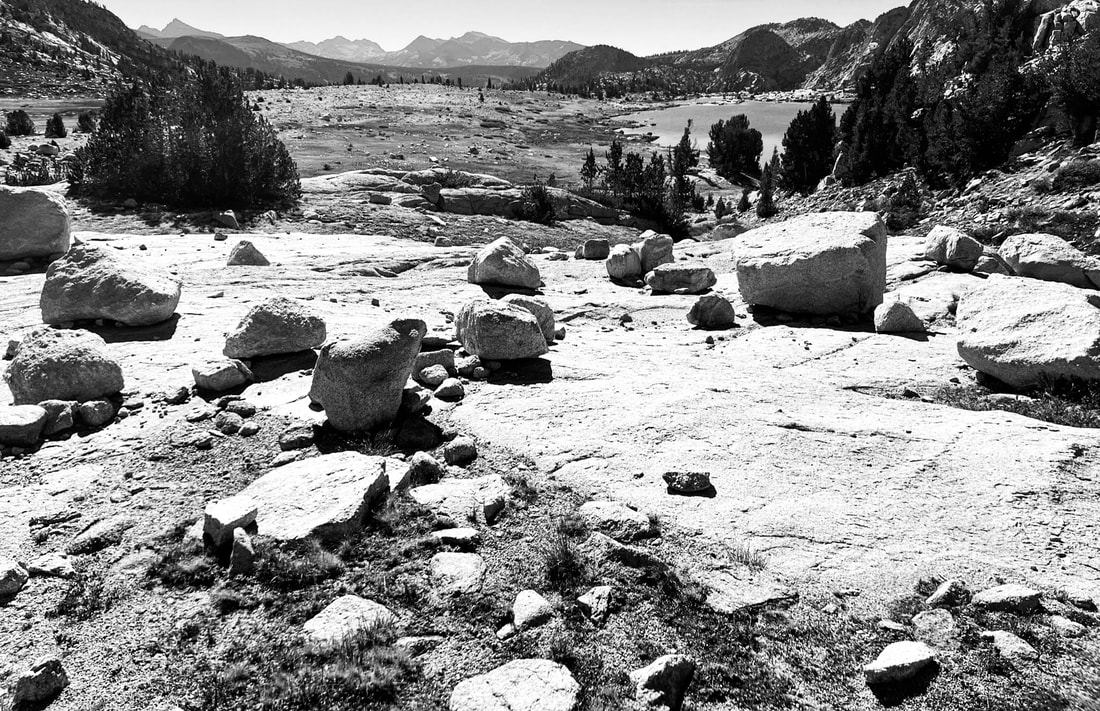

In no time at all we had ascended the 500+ feet to the top of Sanford Col. Looking back on Pioneer Basin (Robber Baron Basin) was spectacular. In the foreground, numerous unnamed lakes, meadows, creeks and sparse vegetation. And in the background, miles of jagged peaks and ridges making up the four Mono Recesses and beyond.

Turning around and looking over the other edge was quite a different view. Looking down we could see three things over the next 3/4 of a mile. Rocks, rocks and more rocks. And the first 150 yards was steep. Extremely steep. Luckily, the lingering snow on the top on the northern side was powder soft and not ice. Ice could have been catastrophic.

We spent about 15 minutes walking each direction from the actual Col looking for what we would determine was the best route down. Never would we really know if we chose correctly.

We chose to start our descent not from the true Col, the lowest point of the saddle, but from an area about 40 yards higher and to the west. It fed into an area with bigger rocks rather than into a sand filled chute at the Col. Pablo went first and we navigated slowly around a corner that we couldn't see past. Our thought was that if we got to that corner and saw that there was no safe way to go further, we could get back up to the top without much trouble or danger and reevaluate from there. As we got to the corner we could see that what lay ahead wasn’t much different than anything else we had seen while scouting it from the top. We decided to commit. This would be our route.

As we started down two things became quite clear. One, we could trust no one rock no matter how big or small. Anything could and did move. We needed 3 points of contact at all times. Two, we would not be able to take the same line or even close to the same line. We were both knocking enormous rocks loose that would have taken either of us completely off the mountain had one hit us from above. So we spread out to the tune of about 30 yards apart.

We each took up a different technique. While Pablo was more comfortable going backwards like on a ladder, I was more comfortable going forwards like a staircase. We would start and stop and check on each other constantly and finally arrived at the top of the bowl. Now that the dangerous part was over, it was time for the part that would pound our bodies into submission. An endless sea of boulders and talus lay ahead. Neither of us would take a single picture in this area. Every step was a decision. The only time we could look up is if we stopped. Otherwise we were micro navigating from rock to rock while hopping from one to another using both feet and both hands with every move. Our hiking poles had been stored in our packs at the top of the Col.

We each took up a different technique. While Pablo was more comfortable going backwards like on a ladder, I was more comfortable going forwards like a staircase. We would start and stop and check on each other constantly and finally arrived at the top of the bowl. Now that the dangerous part was over, it was time for the part that would pound our bodies into submission. An endless sea of boulders and talus lay ahead. Neither of us would take a single picture in this area. Every step was a decision. The only time we could look up is if we stopped. Otherwise we were micro navigating from rock to rock while hopping from one to another using both feet and both hands with every move. Our hiking poles had been stored in our packs at the top of the Col.

This section was exhausting. In all, it took us about 3.5 hours to go about 2.5 miles where we reached Steelhead Lake and finally an actual trail. (To put that in context, for the rest of the trip we walked 2-3.5 mph) We had a quick snack and decided to wait to get water until a lower creek as we got going again. After a few minutes of trying to find the trail we were off again. And then it happened again. But this time it was my left ankle. I went down once again. And once again, bad but not terrible. Now I had a right ankle that was still painful with certain steps and a left ankle that was painful with every step. Damn.

We continued down a very steep trail back to McGee Creek and we got water and had a snack. We didn’t linger as we were both spent and hungry and were looking forward to the trailhead and The Barn in Bridgeport. At this point we had about 5 miles left and were within striking distance of both. We hiked on. At about 3 miles out we caught two other backpackers, the first people we had seen in over a day and a half. We chatted for a couple minutes and went on ahead of them. Later we would see a couple day hiking and still later another couple. Pablo was quite a bit ahead of me as I was being extra careful and walking slowly. As I approached the last couple, my left ankle went again and I was on the ground. It scared the heck out of the two as I popped up and got going as quickly as I could. The last almost 3 miles would be not only painful but mentally draining as I was doing everything in my power not to twist again.

Within about a quarter of a mile from the trailhead I caught up with Pablo. We finished together and after a celebratory fist bump we each got cleaned up before hitting the road. We arrived at The Barn in plenty of time before they closed (this time) and enjoyed our food as always.

It was an amazing trip. Pablo called it “beautifully intense” and I couldn’t agree more. Yes, the millage was off on day one, but in the end it was the north side of Stanford Col that really took its toll. It’s just another example of why it’s so important to spend adequate time before a hike looking closely at maps and planning. And it’s a reminder that when planning, if I ever see anything close to a ¾ mile stretch of trail-less rock and talus, to either find a way around it, or plan an alternate route for sure.

It was an amazing trip. Pablo called it “beautifully intense” and I couldn’t agree more. Yes, the millage was off on day one, but in the end it was the north side of Stanford Col that really took its toll. It’s just another example of why it’s so important to spend adequate time before a hike looking closely at maps and planning. And it’s a reminder that when planning, if I ever see anything close to a ¾ mile stretch of trail-less rock and talus, to either find a way around it, or plan an alternate route for sure.